When Nelson Khethani moved to Johannesburg in 1980, he was struck by how clean the streets were.

Living in the central Berea neighbourhood of South Africa’s largest city through the 1990s and 2000s, after apartheid was dismantled, he recalls his homes being in “very, very beautiful buildings”.

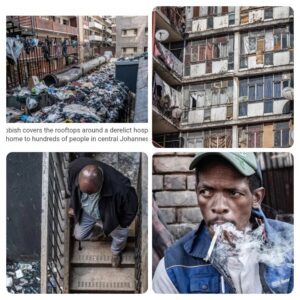

Such memories are painful to reconcile with the city centre squalor Mr Khethani now endures.

The lower floor of his current accommodation in Joubert Park is heaped with uncollected rubbish and reeks of human waste. No one comes to clean or to empty the filth, and the overcrowded floors are full of criminals and sex workers, he says.

The streets around his home are crumbling into deep potholes, and drug dealers and robbers menace the area.

Mr Khethani’s block is not the only one to have fallen into such a state. Formerly well-to-do city centre neighbourhoods, including Hillbrow and Berea contain many in the same condition.

This is a side of Johannesburg that South Africa will not be showing off to world leaders attending next month’s G20 summit in the city.

“I’ve seen it change so much over the years,” Mr Kethani, 74, says.

The decay is entrenched. Some neighbourhoods, in a place colloquially known as the City of Gold, have been without water for weeks as decrepit infrastructure gives up. Residents say local government services in the city, the capital of Gauteng, South Africa’s wealthiest province, are in freefall.

“Johannesburg is on the verge of becoming a failed city, almost like a failed state, like many African failed states at the country level,” William Gumede, associate professor at Wits University’s School of Governance, said recently.

“In the case of Johannesburg, a failed city is beset by systemic corruption, lawlessness, infrastructure collapse, and the informalisation and deindustrialisation of the city economy.”

The decline of South Africa’s biggest and wealthiest city and its commercial hub has been under way for decades, but is now dominating national politics as the main opposition party tries to dislodge the ruling African National Congress (ANC).

The ANC’s failure to deliver basic services in places like Johannesburg has contributed to a dramatic slide in its popularity with the party’s share of the national vote falling from 58 per cent in 2019 to 40 per cent last year.

The opposition, the Democratic Alliance (DA), which has been in a unity government since the ANC lost outright power last year, smells blood.

After evicting the ANC from more than three decades of majority national rule, the DA now thinks it can oust the party from city halls in next year’s municipal elections.

Johannesburg is a key target and the party has put up one of its most formidable campaigners as a mayoral candidate.

Helen Zille has been described as South Africa’s Iron Lady, and is an anti-woke campaigner. She has also been given the nickname “God-Zille”.

The 74-year-old former mayor of Cape Town and former premier of the Western Cape says she is running to save the city where she was born and began her career.

“It is daunting, I am not going to lie, it’s extremely daunting, but someone has got to do it,” she told The Telegraph on a tour of the city centre.

“The DA is the only party that can fix Johannesburg and our big challenge now is to convince the voters.”

Johannesburg city centre is not uniformly run down and, like in many cities, conditions can change dramatically in a few hundred yards. Less than a mile from some of the most run-down areas, hipsters drink in fashionable new Braamfontein bars, and elsewhere the city has some of Africa’s most affluent business and residential districts, such as Sandton and Rivonia.

Yet even the president, Cyril Ramaphosa, was earlier this year forced to concede that the once-mighty central business district appears filthy and “torn apart”.

The decay has appeared to accelerate in the past two decades, despite efforts to spruce up the city for the 2010 World Cup, when the country spent a total of £2.4bn on stadia and upgrades to roads and airports.

Johannesburg “is teetering on the brink, with infrastructure collapsing, frequent water and power outages, and rubble piling up”, says Prof Gumede.

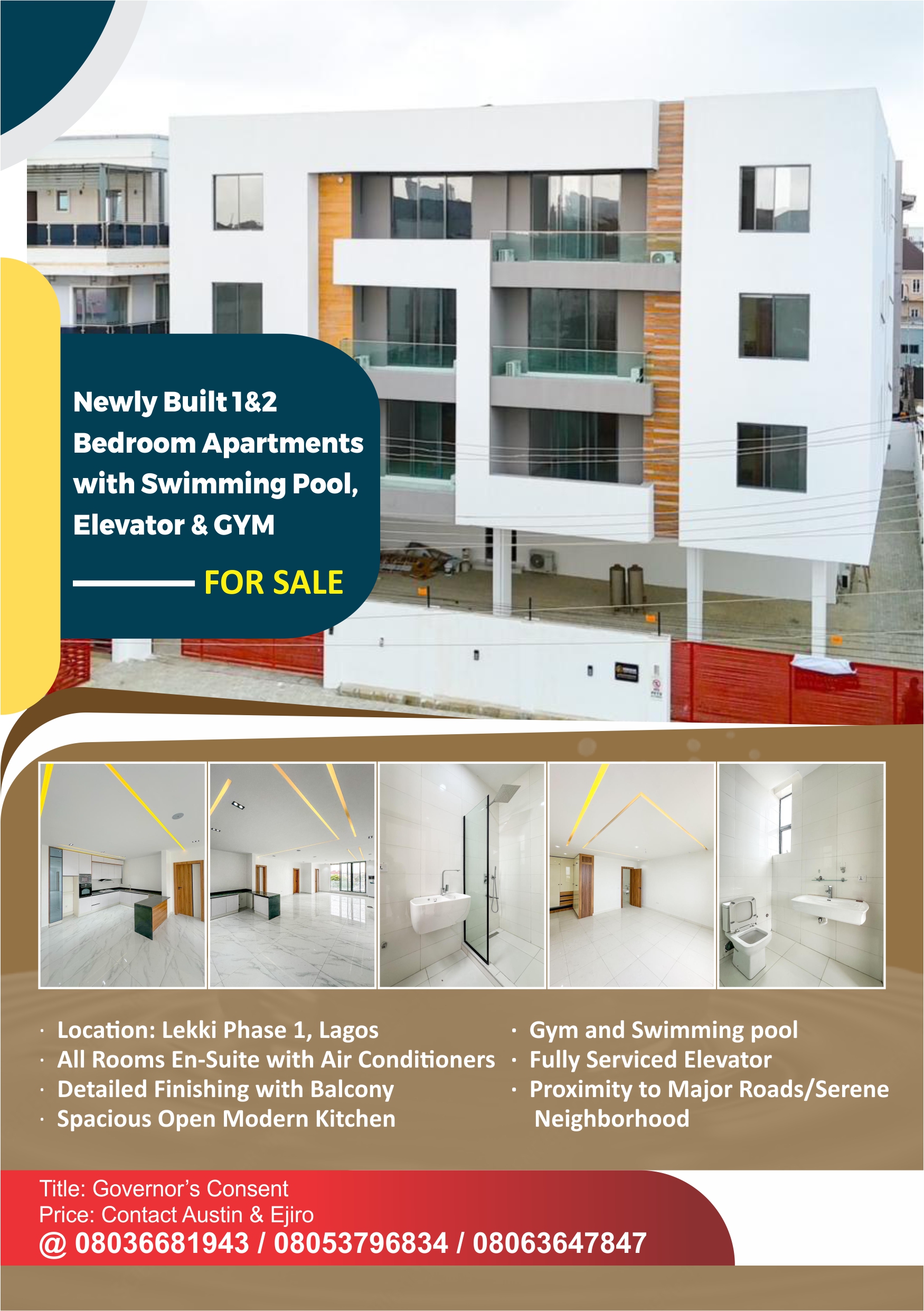

Among the city’s pressing problems are hundreds of “hijacked” buildings: empty or neglected properties taken over by gangs who fill them with tenants.

National unemployment is around 33 per cent and there is a severe shortage of housing.

Wealthy residents and their tax revenue depart as the situation worsens.

A street drug called Nyaope, a mix of heroin, cannabis and HIV antiretroviral drugs, is rife and drives much of the crime.

The collapse in public services means rubbish is not collected, roads are not fixed, and year by year things get worse. Earlier this year, it was reported that 45 of the 120 bin lorries in Johannesburg were broken down.

Images from Google’s Street View app are used by one widely followed social media feed called Jozi vs Jozi to provide a chronicle of the decay.

The city recently had 97,715 reported power cuts over nine months, with more than 5,000 serious enough to take out whole suburbs.

The biggest problem of all is water, says Ms Zille, with some neighbourhoods finding their taps non-functional for weeks at a time.

Ahmed Timol, a resident of the Crosby neighbourhood, which is west of the city centre, said taps there started running dry three years ago. Usually, it was overnight, but at its worst, it was for several days straight.

Service was so bad that houses built their own boreholes to share with neighbours, or got water from taps in mosques.

He said: “Everything is an issue. You have to do your own thing.”

Ms Zille says: “The water infrastructure has not been maintained for 30 years and it’s crumbling.

“If you can’t deliver clean water to citizens in a major city then you have got Apocalypse Now. It’s very hard to live without electricity, but it’s impossible to live without water.”

The ANC knows its record of failing to deliver services is a potentially fatal electoral liability and Mr Ramaphosa has urged ANC officials to do better.

But Johannesburg is not the only South African city in trouble.

Last week, Ashor Sarupen, a deputy finance minister, said the country’s main municipalities – with the exception of Cape Town – were in a “death spiral”, spending too much money on staff salaries and too little on maintaining and building infrastructure.

The main problem is not incompetence, but corruption, the DA alleges. Funds that should go on infrastructure and public services are siphoned off.

Ms Zille says: “It’s got like this through administrations that considered the city as a massive employment bureau for what the ANC calls cadres and comrades, and a massive capital extraction feeding trough for connected individuals and by every other kind of corruption that you can possibly think of.”

“What you have to do is overhaul the entire system and find out exactly what decisions are taken and whether the projects advertised for tender are actually needed or whether they are just a cover for enriching some people.”

In one of the most damning examples of such corruption, health officials and politically connected criminal syndicates are accused of creaming off £86m from Tembisa hospital, just outside the city.

A senior health service accountant called Babita Deokaran, who flagged up suspicious spending in 2022, was shot dead.

Ms Zille expects a ferocious fight for the mayoralty.

The ANC may name its own big gun candidate and try to raise the issue of race, which is never far from South African politics. The DA has a reputation as a white-led party and Johannesburg is more than three-quarters black.

Ms Zille says: “In South Africa, people have to make the choice; do they want to make it about race and live without water and electricity and all sorts of other things, or do they want the stuff fixed? It’s a very simple choice.

“And I think that in this election, a lot of people are going to make the shift to service delivery for the first time.”

The ANC this week insisted that under its mayor, Dada Morero, it was turning the city centre around. “Hillbrow is steadily reclaiming its place as a vibrant and liveable part of our city,” it said.

Mr Khethani disagrees.

“The ANC of today is not the party of Mandela or [Thabo] Mbeki,” he said.

“There are councillors and there’s a mayor. They are getting paid at the end of the month for doing nothing.”