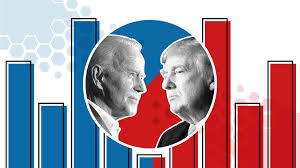

Americans who go to the polls on Election Day don’t actually select the President directly.

They are technically voting for 538 electors who, according to the system laid out by the Constitution, meet in their respective states and vote for President and Vice President. These people, the electors, comprise the Electoral College, and their votes are then counted by the President of the Senate in a joint session of Congress.

Why did the framers choose this system? There are a few reasons: First, they feared factions and worried that voters wouldn’t make informed decisions. They didn’t want to tell states how to conduct their elections. There were also many who feared that the states with the largest voting populations would essentially end up choosing the President. Others preferred the idea of Congress choosing the President, and there were proposals at the time for a national popular vote. The Electoral College was a compromise.

The stain of slavery is on the Electoral College as it is on all US history. The formula for apportioning congressmen, which is directly tied to the number of electors, relied at that time on the 3/5 Compromise, whereby each slave in a state counted as fraction of a person to apportion congressional seats. This gave states in the South with many slaves more power despite the fact that large portions of their populations could not vote and were not free.

How it works

There’s an elector for every member of the House of Representatives (435) and Senate (100), plus an additional three for people who live in the District of Columbia.

Each state gets at least 3 electors. California, the most populous state, has 53 congressmen and two senators, so they get 55 electoral votes.

Texas, the largest reliably Republican-leaning state, has 36 congressmen and two senators, so they get 38 electoral votes.

Six states — Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming — are so small, population-wise, that they only have one congressperson apiece, and the lowest possible three electoral votes. The District of Columbia also gets three electoral votes. Voters in Puerto Rico and other non-state territories get no electoral votes, although they can take part in presidential primaries.

The states are in charge of selecting their own electors. And a number of states do not require their electors to honor the election results, which has led, occasionally, to the phenomenon known as a “faithless elector.”

It takes 270 electoral votes to get a majority of the Electoral College. The total number of electors — 538 — cannot change unless there are more lawmakers added on Capitol Hill or a constitutional amendment. But the number of electors allocated to each state can change every 10 years, after the constitutionally-mandated Census.

However, the Electoral College is written into the Constitution and changing the Constitution is very difficult. It takes years to accomplish and requires broad majorities in Congress or state legislatures. States that currently benefit from the Electoral College would have to give up some of that power. The other possibility is something like to honour the national popular vote winner. But you can bet if that proposal takes hold, there will be lawsuits.

The Electoral College has actually changed three times, each by constitutional amendment. The 12th Amendment, passed after the tie election of 1800 made it so that electors voted for President and Vice President instead of voting for two people who could be President. The 20th Amendment put a time limit on the process. The 23rd Amendment gave electors to the District of Columbia.

And there was a serious move decades ago to abolish the Electoral College altogether. In 1968, a proposal to replace the Electoral College with a popular vote system easily passed in the House. It was filibustered in the Senate.

The Electoral College votes assigned to each state.